First, Some housekeeping: I’m teaching a 5-week course starting on July 14 on Writing the Nonfiction Book Proposal. Designed for writers at all stages of the book proposal development process, we'll analyze several real proposals that successfully sold and hear from award-winning authors Lauren Markham and Elisa Gabbert about how they wrote, sold and used their proposals in drafting their manuscripts. We'll also hear from my editor at Graywolf Press and my agent at Transatlantic on how they evaluate proposals in a teeming literary landscape.

You’ll leave the course with a draft or detailed outline of your own book proposal, as well as a solid understanding of what makes a winning proposal. Learn more and sign up here.

Now, onto the meat of this post. Earlier this year, I saw the political science scholar and Zohran Mamdani’s dad, Mahmood Mamdani, speak at Makerere University in Uganda. It was a poignant homecoming: born to Indian Gujurati immigrants, Mamdani Senior grew up in Uganda and went on to teach at this very school for many years. Old colleagues and students rushed to clasp his hand and murmur their greetings. The room was full to bursting. People literally lined up outside and listened to Mamdani speak through the open windows.

Unfortunately, Mamdani delivered the lecture, which focused on customary land tenure in Uganda, in heavy academic jargon. Much of it went over my head, but two moments from that afternoon stood out.

He opened by confessing he was ill-prepared to speak that day as his house in Kampala was robbed three nights earlier. The thieves took only his laptop and his backpack. Nothing else. “Maybe they were making a statement about what they were interested in,” he said. More likely is that the powers-that-be were sending him a message: don’t make any trouble. But such intimidation tactics couldn’t phase Mamdani Sr. For decades, he’d been a thorn in the Ugandan government’s side, loudly criticizing its disregard for poorer citizens in rural areas, President Museveni’s seemingly never-ending rule (going on 40 years now), and the country’s economic ties with Israel. That kind of public criticism is dangerous in Uganda, where the government regularly jails its naysayers, and it’s especially dangerous for a “mohindi”—a Ugandan of south Asian origin. Uganda had expelled its Asians before, in 1972, and who’s to say the government wouldn’t do it again.

But even that 1972 expulsion didn’t deter Mamdani Sr., 26 at the time: he simply returned to Uganda, albeit 14 years later, and he and wife, the filmmaker Mira Nair, who he met there in 1989, have called it home—or at least one of their homes—ever since. It was in Uganda where their son Zohran was born and lived the first five years of his life. As Jamaica Kincaid said of Antigua, Kampala is a small place. Zohran, even young and privileged as he was, would have felt this smallness, this sense of entanglement with his neighbors and nanny and driver and askari. He would have seen how his life depended on the working class, and he might even have cared for them. The house staff were likely around at least as much—if not more—than his busy parents.

At one point in the lecture, Mamdani Sr.’s water bottle blocked the computer camera so that attendees tuning in on Zoom couldn’t see him. Finally, one of the students got up and moved the bottle. Mamdani stared at him, bemused. “Hm. He must know something I don’t,” he said. Everyone chuckled. He moved on, no further questions asked.

It was a small moment but it struck me as unusual. Here was a leading public intellectual, acclaimed both in East Africa and globally, a tenured professor in Columbia and the author of at least a dozen books. Surely a man of great intellectual curiosity. And yet, he was fine not knowing exactly what drove this young man’s action.

What must it have been like to grow up with that kind of father, I wondered? A man both humble and confident enough to admit he didn’t know everything, and didn’t need to know. A man who, despite several traumas including expulsion from his home and a long period of legal statelessness, could still trust so easily. Could just be at ease period.

It's not hard to see where Zohran got his confidence.

Living as I do in the middle of the US, I have at times found the incessant coverage surrounding Mamdani Jr.’s campaign a bit boring. Oh, a hyper-liberal wins the mayoral primary in one of the country’s most liberal coastal cities? Shocking.

I know NYC has suffered more than its fair share of loser mayors funded by big money. But I would have found the whole thing more interesting if it happened in, idk, Utah? Montana? Missouri? Anywhere there’s not on a coast, really.

But I also realize New York was probably the only place where someone like Mamdani Jr. could have come to power. And in that same vein, Mamdani Jr. could only have become who he is thanks to a) his specific parents, and b) his specific roots in Africa.

In 2015, I accidentally met Mira Nair in Kampala. I was attending a friend’s poetry reading at Maisha Gardens, a beautiful green space southeast of the city and overlooking Lake Victoria. After the reading, my friend introduced me to “Mira,” a short Asian woman with a sleek bob, sunglasses and a black silk scarf. It wasn’t until later that I realized I’d met Oscar-nominated director Mira Nair, or that she’d built the green space my friend performed in that day.

The garden was part of Maisha Film Lab, a nonprofit that Nair founded in 2005 to train and mentor East African filmmakers. Almost every East African working in the industry today has come through the Lab, including Lupita Nyong'o (!!) and Moses Bwayo, whose 2022 documentary “Bobi Wine: The People’s President” was nominated for an Oscar.

A lot has been written about Nair’s visionary work as a director, including India Cabaret (1984), one of the first documentaries to reveal the exploitation of female strippers in India; Mississippi Masala (1991), following a family of Ugandan-born Indians displaced in Mississippi; and Monsoon Wedding (2001), one of the few films to deal with incest in Indian families. But relatively little has been written about Nair’s contributions to the filmmaking community in East Africa—to nurturing talent who’d go on to tell stories that she herself couldn’t. I imagine her son absorbed that generosity of spirit. Not just generosity but responsibility—to the people they lived amidst, to the place they called home, and to local stories that deserved a wider audience.

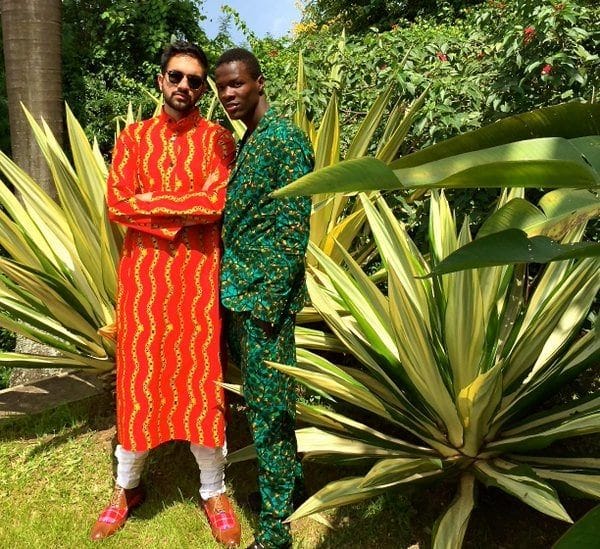

A year or two after meeting Mira, I heard Zohran Mamdani rap at a hotel in Kampala. This was after he’d earned a degree in African Studies from an American liberal arts college, and before entered New York politics. In those interim years, he tried to make a go of it as a rapper in East Africa, adopting the stage name “Young Cardamom.” His first single “Kanda [Chap Chap]” uses chapati—an Indian dish brought to East Africa by immigrants like his grandparents—as a way to discuss identity, migration, and pride.

Great in theory but in practice, Young Cardamom was…not very good. I remember scanning for an exit before he even finished his second song.

Still, I admired Mamdani Jr.’s willingness to put himself out there, to try and fail in public, and to do what other few other south Asians had dared to do in that country. It’s all the same qualities that won him New York’s mayoral primary: the willingness to do what few privileged people, especially south Asians, in this country will do. To advocate for the working class at the expense of the wealthy. To call a war crime a war crime. To make himself inconvenient to power and undeniably worthy of immigrants, unions, and progressives’ trust. Clearly, he inherited at least some of these qualities from his parents, and also from the land where he took his first steps.

“Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past,” writes Saidiya Hartman. “Inheritances are chosen as much as they are passed on." Mamdani Jr. was blessed with the inheritance of not only a radical politics from his parents, but also humility and a sense of self larger than the individual that accompanies being from a small place.

Zohran Mamdani could have turned away from these inheritances. He could have studied finance, become a banker, bought a Cybertruck. But he didn’t. He turned in, all the way in, and New York, you wonderful annoying city, I’m so very glad for you.

Awww I love your writing and your personal insights into this. I did not know much about him but I had the same thoughts as you, only in NYC can someone like him rise up. When I looked him up, his life story sounded fascinating and unique... yet those are the same life experiences that are being attacked as un-American now. Thanks for sharing more about his life outside NYC. I love having that insider glimpse into his surroundings pre politics.

When I first heard about Zohran last fall, I immediately thought of his parents and their incredible work, respectively. Thank you for sharing your perspective and experience. You're the first writer I've seen dig into their history in East Africa!