Against hope

Why make art under oppression?

You know it’s bad when even the whites aren’t safe. Last week, a white TV producer was thrown to the ground, arrested and detained by federal agents in Chicago. Of course this followed an unknown but undoubtedly staggering number of illegal arrests and deportations of Latino and other BIPOC journalists, veterans, undocumented residents, children and American citizens.

I know many people around the world live and have lived for decades—maybe even their whole lives—under authoritarian regimes. I know life goes on in those places as it must: people share meals and have babies and buy homes. I’ve lived in some of these places myself but I’ve always been protected by my status as an outsider, my ability to flee if things got really bad. This feels different, though I know I’m still far less at risk than many of the people building our houses, growing our food, delivering our takeout. The fact remains that these days, there are only two instances when I’m not enveloped by terror or rage: one is when I’m disassociating (thank you childhood trauma). And two is when I’m researching my book.

It’s strange: I’ve always thought of writing as an act of hope, an argument for the world you want to see, a vision of its contours. And I know the abolitionist Mariame Kaba says that hope is a discipline. But I guess I’m not very disciplined these days.

I still donate to my local dog rescue, pay for some news subscriptions (even if I can hardly bear to read them), and try to always have cash on hand for the Venezuelan guys selling flowers or washing windshields in Denver. But I don’t feel hope in these actions, only despair.

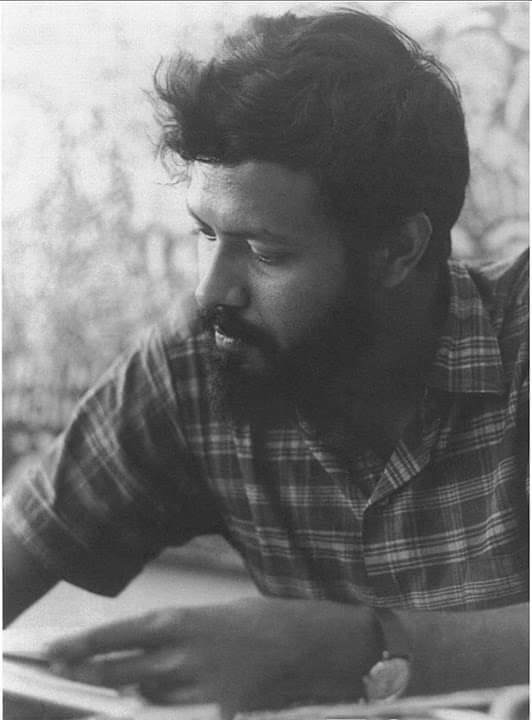

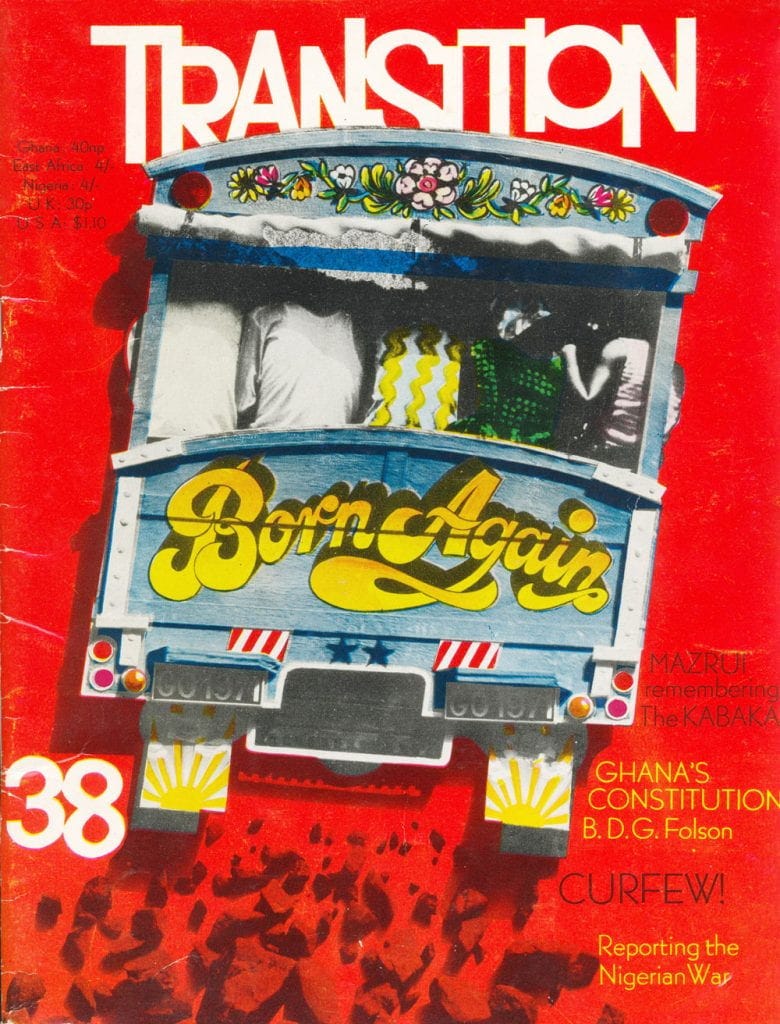

For my book, I’ve been researching a man named Rajat Neogy. Neogy was born to Bengali parents in Uganda in 1938. At the age of 22, he founded Transition, which would go on to become one of Africa’s leading political and culture magazines, launching the careers of writers like Wole Soyinka, Ali Mazrui, Peter Nazareth and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. He even convinced Langston Hughes, Nadine Gordimer, and James Baldwin to write for him, connecting the struggles for civil rights in America and South Africa to those in newly independent African nations.

“The idea is really to see and feel and hear what contemporary East Africa is doing, thinking, and acting upon,” Neogy said. Over time, Transition’s scope broadened beyond East Africa to encompass other parts of the continent and beyond—namely south Asia and the Black community in America.

Neogy was a hands-on editor (“here’s what I want you to do”) and prided himself on being an “an irritant,” a provocateur, a source of what he saw as necessary friction within and across political, intellectual and racial lines. That’s exactly what made the magazine so compelling (In 1968, the New York Times applauded the “questing irreverence [that] breathes out of every issue”). In defiance of several African governments’ wishes and even threats, Neogy published biting critiques of of Tanzania’s deportation of a South African journalist, of book bans and media censorship in Kenya, and of President Obote’s changes to the Ugandan constitution.

In October 1968, Neogy was arrested on charges of sedition by President Obote. The jails were full of political prisoners but he could not commune with any of them. He spent five months in solitary confinement. The experience shattered him.

“The most frightening thing about detention is its arbitrariness and its suddenness,” Neogy wrote. “Like death, you think it only happens to other people.”

Seen through the archives of Transition, the parallels between 1960s Uganda and contemporary America appear numerous and terrifying: censorship, arbitrary arrest and detention, sudden and illegal stripping of constitutional rights, a culture of government impunity. But what to do with this information? How do we act knowing we’re not the first to face such circumstances?

Knowing he could no longer publish the magazine the way he wanted to in Uganda, Neogy chose to leave his homeland in 1969. The authorities immediately stripped him of his citizenship. It broke him. He started drinking heavily, flitting between London, America and Greece. Finally in 1970, he resettled in Ghana, where he threw himself into relaunching the magazine. But deprived of his beloved Uganda, his drinking worsened. In 1974, after his wife left him and took their kids, he realized he couldn’t go on the way he was. He handed over editorship of Transition to Wole Soyinka, the future Nobel Laureate, and flew to permanent exile in San Francisco.

For a while, Neogy published a community newspaper and worked as a taxi driver. He moved into a public housing space with shared bathrooms. He read and drank in his small single room.

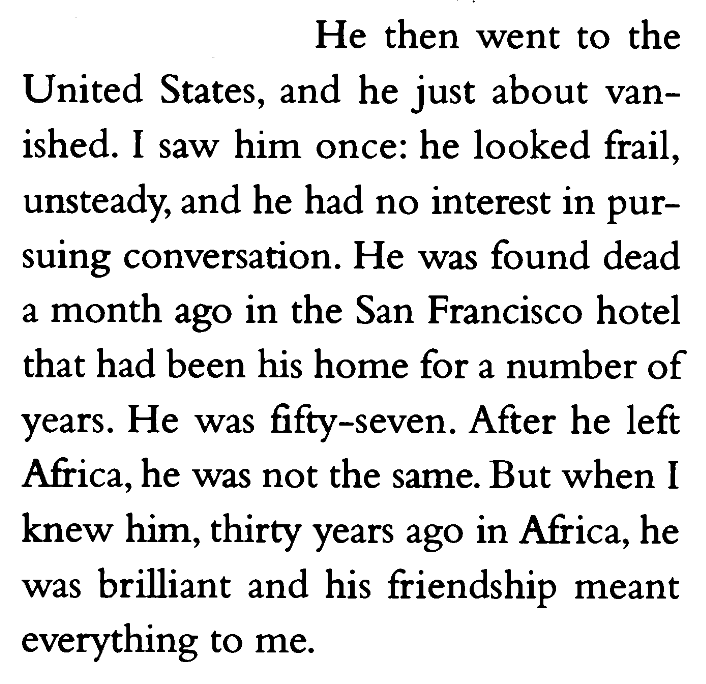

At the end of November 1995, Neogy called each of his seven children, most of whom he was estranged from. On December 3, he was found dead in his room, two days after he’d died. He was holding his phone book in his hand. He was 57.

Meanwhile, Transition lives on. It’s now housed at Harvard, and it still publishes some of the best English-language prose, poetry, criticism, photography and art from the African continent. I read the latest issue with as much pleasure as its earliest issue.

I’ve now read every interview Neogy ever gave, every piece he ever wrote, and most of the issues of Transition he edited. I’ve also spoken to his daughter and visited the hill in Kampala where he lived, searching for some remnant of his spirt.

In doing all this, I was trying to make sense of his life: was it a model of hope and solidarity or its opposite? He loved East Africa and its people in a way that was rare for the business-minded South Asian diaspora there, especially in the 60s. And yet this same love unraveled him, exile corroding his soul and stripping the value from everything else in his life: his family, his friends, even from literature. And yet his magazine lives on, continuing his mission of documenting contemporary African art, politics and culture.

Obviously alcoholism is a disease without clear cause. But having grown up with an alcoholic father, I have some sense of what drives it, especially in middle-aged south Asian men. I think the hope for a different reality, a return to what once was, drove Neogy not only to drink but to estrange himself from all that the present could offer. He never got over his hope that he could one day return to the Uganda of his past. Just like my father never got over wanting to return to being a light-skinned Brahmin man in India—nearly a god—instead of just another brown-skinned immigrant in western Canada.

If hope is the thing with feathers as Emily Dickinson writes, then it’s also the thing with talons. They dug deep into Neogy and my father, paralyzing them.

What am I trying to say? I suppose it’s this: you can make and find meaning even—and perhaps especially—in the absence of hope.

In the face of a collapsing country AND a crumbling publishing industry, I no longer harbor the hope that my book will change the world or be read by the masses. I don’t hope it will receive glowing reviews from prestige media, that it will hit the bestseller lists or win awards.

But paradoxically, this draining of hope has sharpened the meaning of my work. It has reminded me that writing is not about changing others’ minds but my own. And every day I work on my book, I do feel my mind change, sometimes dramatically, sometimes almost imperceptibly, just a cloud inching over the sun. But I feel it.

I might be wrong about the reasons for Neogy’s decline. But his legacy is clear, a reminder that documenting an era from one’s specific lens is vital in and of itself. That even if this planet lies in ruins one day, my record will live on and someone in the future might find it. That it might not offer them hope but it will offer them a connection to what once was: a cruel and degraded world that I loved anyway.

Raksha, I’m so grateful to know you and follow your work. Your writing is powerful and moving. Hopelessness is all around, but writing like yours lifts up spirits and recenters mindsets. Misery loves company and reading how people like you (caring and insightful) are coping or at least processing is nothing short of reinforcements for the discipline of hope.

This is such wonderful writing. I'd never heard of Neogy. Thank you for introducing me to him. I will seek out his writing. His sad ending reminds me of what Hemingway endured. Will humans ever stop the political oppression? Thank God for artists and others who are willing to stand up and speak the truth, even when it costs them so much.